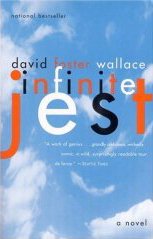

Book Review: Infinite Jest

Perhaps my favorite book is Infinite Jest, by David Foster Wallace. It's huge and unwieldy and often incoherent. It has 1088 pages, including 96 pages of small-type footnotes. There's no climax to speak of. (Despite ignorant reviewers, this is intentional and essential.) You'll need an unabridged dictionary for a word on nearly every page.

Perhaps my favorite book is Infinite Jest, by David Foster Wallace. It's huge and unwieldy and often incoherent. It has 1088 pages, including 96 pages of small-type footnotes. There's no climax to speak of. (Despite ignorant reviewers, this is intentional and essential.) You'll need an unabridged dictionary for a word on nearly every page.You'll either love or hate the language. Here's a test: if you are not turned off by the title of my favorite DFW essay, "Tennis Player Michael Joyce's Professional Artistry as a Paradigm of Certain Stuff about Choice, Freedom, Discipline, Joy, Grotesquerie and Human Completeness" (collected in A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again) you might like Infinite Jest.

It's not a beautiful book; there are no lyric descriptions of love and beauty. It's about addiction and depression and the futility and inadequacy of intelligence and success. It takes place primarily in a tennis academy and a rehab clinic. It's also, in part, a retelling of Hamlet.

I can't explain exactly why I loved this book, but it goes beyond my (immense) enjoyment of his writing style. I think it's just a book that manages to not only get at the sadness and futility that so often accompanies the (post-) modern age, but to get through to people like me -- the intelligent, the skeptical, and the jaded. DFW plays all the pomo games -- the self-reference, the allusions, the ironic detachment -- but he does it to get through to a generation that uses that stuff to build walls around ourselves to avoid feeling anything real.

Here's DFW in an interview:

[Interviewer:] Not much of the press about "Infinite Jest" addresses the role that Alcoholics Anonymous plays in the story. How does that connect with your overall theme?

[DFW:] The sadness that the book is about, and that I was going through, was a real American type of sadness. I was white, upper-middle-class, obscenely well-educated, had had way more career success than I could have legitimately hoped for and was sort of adrift. A lot of my friends were the same way. Some of them were deeply into drugs, others were unbelievable workaholics. Some were going to singles bars every night. You could see it played out in 20 different ways, but it's the same thing.

Some of my friends got into AA. I didn't start out wanting to write a lot of AA stuff, but I knew I wanted to do drug addicts and I knew I wanted to have a halfway house. I went to a couple of meetings with these guys and thought that it was tremendously powerful. That part of the book is supposed to be living enough to be realistic, but it's also supposed to stand for a response to lostness and what you do when the things you thought were going to make you OK, don't. The bottoming out with drugs and the AA response to that was the starkest thing that I could find to talk about that.

I get the feeling that a lot of us, privileged Americans, as we enter our early 30s, have to find a way to put away childish things and confront stuff about spirituality and values. Probably the AA model isn't the only way to do it, but it seems to me to be one of the more vigorous.

[Interviewer:] The characters have to struggle with the fact that the AA system is teaching them fairly deep things through these seemingly simplistic clichés.

[DFW:] It's hard for the ones with some education, which, to be mercenary, is who this book is targeted at. I mean this is caviar for the general literary fiction reader. For me there was a real repulsion at the beginning. "One Day at a Time," right? I'm thinking 1977, Norman Lear, starring Bonnie Franklin. Show me the needlepointed sampler this is written on. But apparently part of addiction is that you need the substance so bad that when they take it away from you, you want to die. And it's so awful that the only way to deal with it is to build a wall at midnight and not look over it. Something as banal and reductive as "One Day at a Time" enabled these people to walk through hell, which from what I could see the first six months of detox is. That struck me.

It seems to me that the intellectualization and aestheticizing of principles and values in this country is one of the things that's gutted our generation. All the things that my parents said to me, like "It's really important not to lie." OK, check, got it. I nod at that but I really don't feel it. Until I get to be about 30 and I realize that if I lie to you, I also can't trust you. I feel that I'm in pain, I'm nervous, I'm lonely and I can't figure out why. Then I realize, "Oh, perhaps the way to deal with this is really not to lie." The idea that something so simple and, really, so aesthetically uninteresting -- which for me meant you pass over it for the interesting, complex stuff -- can actually be nourishing in a way that arch, meta, ironic, pomo stuff can't, that seems to me to be important. That seems to me like something our generation needs to feel.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home